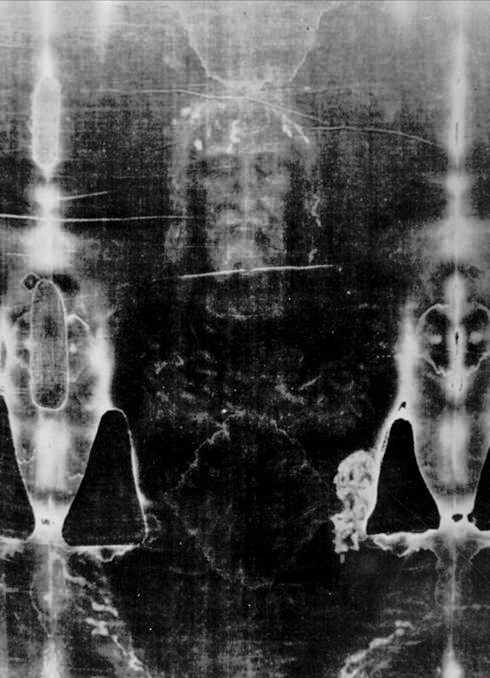

Shroud of Turin is Real Enough

By David Farley | May 13, 2010

The Catholic Church’s most famous (and infamous) holy relic is being exposed to the faithful for the first time since the year 2000. The Shroud of Turin, on display until May 23 in the handsome northwestern Italian town, can be shown by permission only from the pope.

With the unveiling of the shroud, which some believe was the cloth draped over Christ at his burial, comes a revival of controversies: the last test to date the fabric, in 1988, concluded that the shroud was a medieval fake. Then those results were thrown into doubt when it was shown the patch of fabric scientists had tested might have been contaminated. The shroud has also garnered criticism, or rather, snickers and ridicule, because it is an anomaly, a relic not just of a mysterious and revered human being, but also one that has survived the meteoric blast of the scientific revolution, which caused a paradigm shift in human thinking toward skepticism.

The cult of relics is often dismissed by 21st century non-Catholics, but one thing that’s rarely taken into consideration is that scientific tests don’t matter. Lambast the faithful for this antiquated form of worship. Snicker at the sight of someone praying in front of a golden reliquary that houses a shard of bone or a skin fragment from a medieval saint or a pope. It’s an exercise in futility. Case in point: Last autumn, when the relics of St. Therese of Lisieux went on a 28-stop tour of Britain, each stop was overwhelmed with the masses hoping to get a glimpse of the bones of the beloved 19th century nun. More than a million and a half people have already reserved a spot to see the Shroud of Turin for its six-week showing.

Away from relics

The church though, has distanced itself from relic veneration. Relics became ingrained in Catholic Church orthodoxy at the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, when a law was passed stating that every church should have a relic at its altar. That law lasted until 1969 when, in an addendum to the Vatican II reforms earlier that decade, the church officially put the law on altar relics to rest. A few years ago, I called the Catholic church where I attended Mass as a youth, and officials there had no idea what relic (if any) was housed in the church.

I’m not Catholic anymore, but I believe the distancing from relic veneration is unfortunate. For centuries, the Christian faithful have relied on relics to do things that medicine, the government, the lottery and recreational drugs do for us today. And in the 21st century, relics have another power: they are believers’ closest physical connection to the divine. Humans have a need to see the physical possessions of reverence (just look at our celebrity culture today and all the relics associated with it. Graceland, anyone?).

I learned this firsthand when I was doing research on another Christ relic: the circumcised prepuce of the baby Jesus, which had been preserved in a church in the Italian village of Calcata for centuries, until it mysteriously disappeared in the 1980s. People would laugh when I’d tell them what I was researching in the Vatican Library, where I had unearth centuries-old documents detailing the fascinating history of this seemingly unlikely object of veneration. The “holy foreskin” loomed about on the periphery of many historical periods — from the Carolingian dynasty in the early Middle Ages to the Reformation in the 16th century to 19th century romanticism. But as the general public became increasingly skeptical of such “medieval fantasies,” as a priest I interviewed once referred to it, the church itself lost faith in the relic: Pope Leo XIII actually banned the speaking of or writing about this curio in the year 1900 under the threat of excommunication. But people would stop laughing when I’d mention why this relic was so important to believers: It was the only piece of flesh Christ could have conceivably left on earth before he ascended into heaven.

Real in their minds

In a sense, whether or not it was the real flesh of Christ didn’t matter. (Spoiler: It probably wasn’t.) People believed it was authentic (including several popes who granted indulgences to those who came to venerate it). Which is why the hordes of pilgrims who will flock to Turin to pay heed to the shroud will be oblivious to the non-believers’ cackles. If they accept the shroud as the real deal, then, in their minds, in their hearts, in their conceptions of heaven and the afterlife, it is the real thing. They will pray in front of it and it will give them happiness and relief.

And isn’t that what we all want, for ourselves and for each other? Which is exactly why holy relics and the Shroud of Turin still matter in this world.