Who Is A Member of ISKCON? – The Types of Membership

By Kripamoya Das | Jun 16, 2012

<This is the first part of the series of articles exploring the different aspects of ISKCON membership.

Questions people ask me:

Can I become a member of ISKCON? How do I join? What will I have to do? How much does it cost to be a member of ISKCON? How many members does ISKCON have? If I become initiated will I also become a ‘life member?’ If your movement is for everybody why do you have ‘members’ ? What does it mean to be an ‘ex-member’ of ISKCON? Is there another movement called ‘The Real ISKCON?’ or ‘The Greater ISKCON?’ If I’m not in ISKCON can I still be a devotee of Krishna? Can I be initiated but not be a member of ISKCON?

I’m sure that many readers will have asked – or will have been asked – similar questions. It can be a bit confusing in a spiritual movement like ours that is growing rapidly, with an increasingly diverse membership, and one in which the boundaries of the movement are kept deliberately permeable.

People ask me such questions – and many other questions – because they know I have an active interest in expanding ISKCON’s membership. And that’s hard to do if I don’t have at least a working definition of ‘ISKCON membership.’ So I have several definitions of membership, mainly because there’s different ways that people identify themselves as members, and different ways in which the movement may acknowledge people to be members.

(1) Firstly, and it would seem primarily, someone identifies themselves as being a member of any spiritual movement because they are attracted to the ideas. They find themselves in sympathy with the belief system; they discover a group of thoughtful people who – somehow – think about life the way they do; and they have some kind of Aha! moment while exploring the teachings. They want to feel closer to these thoughtful people and wish to be members of the group. This does not require a physical proximity, however, it is more an intellectual joining of minds, something which can happen even over great distances.

(2) Next there is a sympathy with the essential practises of the group. In ISKCON’s case (in my experience) it seems to first manifest as a commitment to vegetarianism, then to kirtan. After this comes experimental japa; then regular attendance to classes and social interaction with devotees, during which there will be time for questions for clarification of the fundamental ideas. After this comes a doubt-clearing period followed by a commitment to daily japa. This is followed by the abandonment of other pursuits which are now categorized as unhelpful to spiritual progress. Then comes the stage – if its not already been reached – of firm friendship with one or several members. Identifying with the essential practices of a group constitutes one form of membership, while having devotee friends – and being accepted by them – itself constitutes membership of a new group, a sub-group of the movement. This type of membership does require physical proximity.

(3) The next type of membership is a little bit subtle, and because of this we might miss it entirely. This is the stage when a person’s value system shifts, incrementally, to accommodate the ethical and moral values of a particular group or movement. Perhaps instead of a shift its more of an adoption of an additional layer of values. As long as the spiritual movement doesn’t do anything to outrage the new members foundational sense of moral decency, then the new member can continue to accommodate a new level of moral values and derive a sense of membership from that.

(4) The next type of membership – and I should hasten to say that these types of membership are not in chronological or hierarchical order – is that of identification with the purposes of the movement. In the case of ISKCON, we are a movement not merely for adherence to the belief system and practises of Vaishnavism, nor even the moral values pertaining to it, but a movement for teaching it to others too.

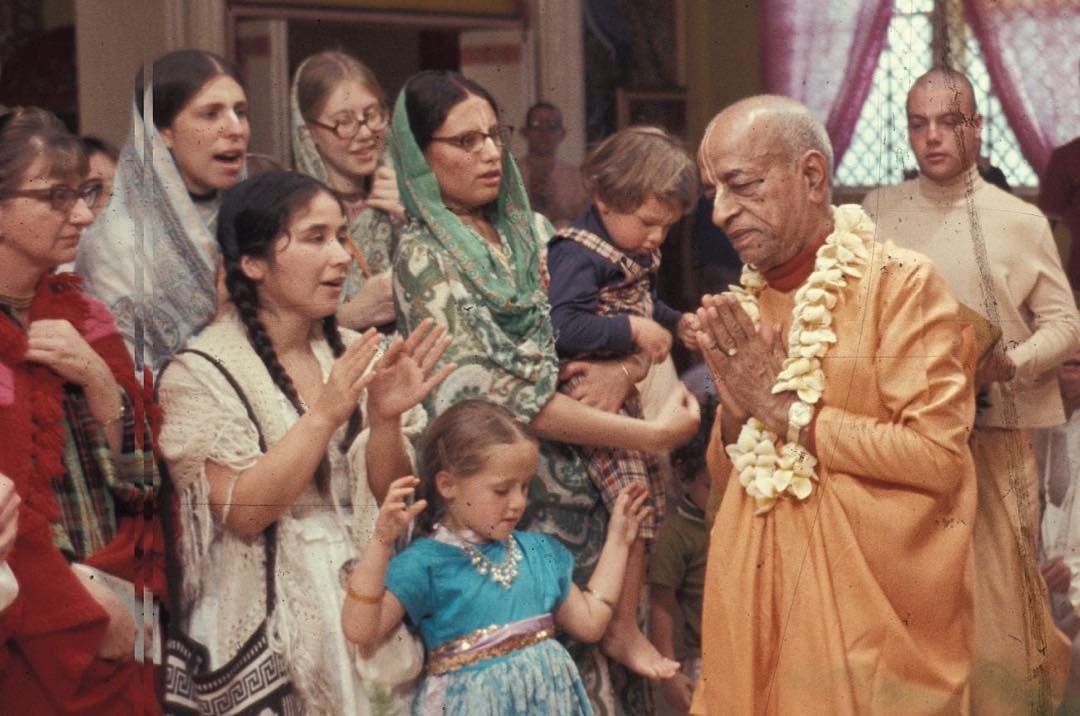

ISKCON is a spiritual movement which has the express purpose of advancing and establishing a body of the beliefs and practices for the good of the world. At the very least, it aims to provide an opportunity for all to explore the teachings and practices, and endeavours to present a persuasive argument that many of the world’s pressing problems (or the psycho-spiritual core of all problems) could be solved with an increase of experiential spirituality. That makes it an educational movement and, since it regards the advancement of religious life to be of help in relief of personal suffering, one which makes it a compassionate and charitable movement too. Indeed, the ‘purposes’ of ISKCON – the very values that underpin its existence – have at their heart the reaching out to others in a compassionate way that the founder exemplified himself. Reaching out to others, then bringing them together so their lives are individually and collectively enriched.

Yet there are those who, although members by virtue of their philosophical convictions and personal spiritual practices, still remain slightly uncomfortable with the notion of belonging to a spiritual movement that actively campaigns and advocates its cause to the public. Even though they themselves have had their lives enriched by such compassionate outreach, they do not identify with all of the purposes of the movement. Those who do recognize the intrinsic value of such ‘systematic propagation’ and like the idea of being a part of a dynamic, campaigning movement, form another category of membership.

(5) There are always people who, in addition to their own beliefs and practices, and in addition to identifying themselves as members of a proselytizing movement, wish to support the good work with practical action. They volunteer their time and financial contributions to help specific projects or the work of the movement as a whole.

(6) The next type of member is the active ‘core’ member. He or she is one of a smaller, organizational sub-group that directly convey the values of the organization to the next generation of members. First comes the ‘active advocate.’ ‘Building for the future’ might be their slogan. Campaigning through writing, publishing, teaching, public speaking, political lobbying, friend-and-fund raising, and media work is one aspect of their contribution to the organization.

Closely related to this work – and intrinsic to it – is the ‘thought-leader’ member. Inspiration, philosophical astuteness, systematic education, pastoral care, mentoring, protecting the new convert, preparing them for initiation, and initiating them is the contribution of this type of member.

The final aspect of ‘core’ membership is the ‘governance’ member. Since it takes decades to grow a spiritual movement such as ISKCON, and since it can be destroyed in a matter of weeks through corruption, scandal, poor planning or leadership failure, the governance – moral, financial and spiritual – must be of a correspondingly high order. And although it is a spiritual movement not a commercial operation, still there must be excellent management in order that the vitality of the organization is not squandered.

All types of member are absolutely valued and essential to healthy growth. Like growth of any biological organism, deficiency in one type of member can lead to weak or inhibited growth patterns. However, it must be said that people do not fit neatly into six segmented types of membership. Their membership identity and active contributions can range over all six types, from time to time, and in varying degrees.

Although no one type of member is worth more than another, still if the core work is to go on it will require a good ratio of supporting members to core members. Members will need to be committed in whatever they do, and people will need to have their own self-identity as a member acknowledged by others.