Doctors of Happiness

By Ravindra Svarupa Dasa | May 30, 2009

The latest findings of Dr. Daniel Gilbert, a Harvard psychology professor both funny and smart, derived from assiduous research into (human) happiness, have revealed to him an important truth that will already be familiar to students of ÅšrÄ«mad BhÄgavatam.

That venerable text recounts (in Chapter 82 of Canto 10) a discussion among certain learned personages—doctors in the original sense of the term—who dwelt on the planet called Janaloka, which can be regarded as the Harvard of our entire cosmos. During this celestial colloquium, one of the sages tells how, at the beginning of creation, the Vedas in personal form (Åšrutis), awaken MahÄ-Viṣṇu from his mystic slumber by hymning him with the very knowledge they themselves embody or personify.

The Sanskrit word veda means knowledge. Although any valid knowledge is veda, in the strict sense veda denotes the uncreated and eternal knowledge on the basis of which the entire material creation is produced by MahÄ-Viṣṇu (and his agents). The world is designed according to prior Vedic knowledge, as engineers assemble an aircraft from blueprints. Veda is not to be confounded with the “knowledge” we humans work up from our investigations of the world and our picayune efforts to reverse-engineer bits of creation.

All the same, a humble laborer in the human knowledge-factory like Professor Gilbert sometimes stumbles on truth, and there is truth to be found in his well-received book Stumbling on Happiness. This truth is conveyed in the title of his recent blog posting “What You Don’t Know Makes You Nervous,” reprinted on the op-ed page of the May 20th issue of The New York Times.

Our unhappiness, Professor Gilbert finds, arises not so much from our present circumstances, exiguous though they may be, as from our anxieties concerning our future. We have a neural mechanism that can keep us happy even in difficult times, he argues; it is fear about the uncertainties of the future that renders people anxious and miserable.

Dr. Gilbert is certainly correct.

Here, from the BhÄgavatam (10.87.32) is the statement of the Åšrutis to the Lord:

The wise, who understand how your mÄyÄ utterly bewilders all people, devote themselves completely to you, the source of liberation. How could the terrors of existence afflict your faithful followers? For those who refuse your shelter, your furrowed brow manifests the turning three-rimmed wheel of time, which keeps them perpetually in fear.

In this passage, the terrors of existence (bhava-bhayam) are explicitly related to the movement of time, whose rim is composed of three sections—past, present, and future.

ÅšrÄ«la PrabhupÄda puts it succinctly in his commentary to Bhagavad-gÄ«tÄ 10.4-5: “Fear is due to worrying about the future.” He expands on this:

A person in Kṛṣṇa consciousness has no fear because by his activities he is sure to go back to the spiritual sky, back home, back to Godhead. Therefore his future is very bright. Others, however, do not know what their future holds; they have no knowledge of what the next life holds. So they are therefore in constant anxiety.

An interesting Sanskrit word that indicates a state of security, devoid of any anxiety, is ká¹£ema. It is derived from the verbal root ká¹£i, which means to abide, stay, or dwell, especially in an undisturbed or secret residence. Ká¹£ema as a noun means safety, peace, rest, security. The Monier-Williams dictionary tells us that the phrase ká¹£emaá¹ te—“peace or security may be unto thee—”is cited in Manu’s Lawbook as “a polite address to a VaiÅ›ya [merchant], asking him whether his property is secure.”

We encounter the word ká¹£ema in the Bhagavad-gÄ«tÄ 9.22, where Kṛṣṇa avers that for those who concentrate on him exclusively, remaining perpetually fixed in devotion, he bears the burden of their yoga–ká¹£emam. In this compound, yoga—which has a root sense of yoking or joining—means acquisition (of goods, for example), and ká¹£emam means the secure possession of that which has been acquired. Kṛṣṇa, then, promises that for devotees wholely dedicated to and dependent upon him, he himself assumes the burden (vahÄmi) of seeing that they get what they require and securely possess whatever they have gained.

In the commentary, PrabhupÄda elucidates yoga–ká¹£emam in its spiritual context:

Such a devotee undoubtedly approaches the Lord without difficulty. This is called yoga. By the mercy of the Lord, such a devotee never comes back to this material condition of life. Kṣema refers to the merciful protection of the Lord. The Lord helps the devotee to achieve Kṛṣṇa consciousness by yoga, and when he becomes fully Kṛṣṇa conscious the Lord protects him from falling down to a miserable conditioned life.

In other places, PrabhupÄda cites this text as assuring that Kṛṣṇa takes responsibility for even the material necessities of a devotee.

In such cases, the devotee is released from all anxiety about the future.

The word ká¹£ema makes an interesting appearance in the 11th Canto of ÅšrÄ«mad BhÄgavatam, which tells of King Nimi’s meeting with the nine Yogendras, the great liberated sons of Ṛṣabhadeva, who traveled together freely throughout the universe. Nimi asks them (11.2.20) to explicate the Ätyantikaá¹ ká¹£emam—the unsurpassable good or supreme position of peace and security.

The phrase is explained in the commentary to the verse:

According to ÅšrÄ«la JÄ«va GosvÄmÄ« the words Ätyantikaá¹ ká¹£emam, or “the supreme good,” indicate that situation in which one cannot be touched by even the slightest fear. Now we are entangled in the cycle of birth, old age, disease and death (saá¹sÄre). Because our entire situation can be devastated in a single moment, we are constantly in fear. But the pure devotees of the Lord can teach us the practical way to free ourselves from material existence and thus to abolish all types of fear.

Dr. Gilbert sees uncertainty of the future as the source of unhappiness. In his blog, he presents instances in which patients made certain by physicians of a future medical affliction are nevertheless happier than those whom physicians give only the possibility of the affliction.

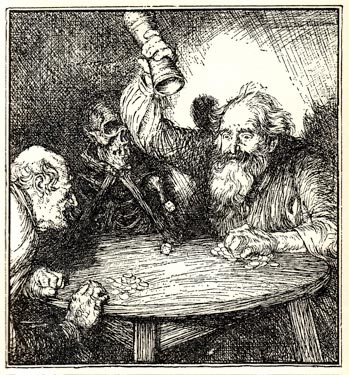

Yet we can understand that such happiness is relative. Anxiety remains. No one knows with any surety what the future will bring, and all face the ultimate unknown death, “the undiscovered country, from whose bourn no traveler returns,” as Hamlet observed in his famous soliloquy. The fear is always with us, try as we will to pay it no mind. As William James noted, not much is needed to bring “the worm at the core of all our usual springs of delight into full view.”

John Updike has a typically stunning metaphor: “We all dream, and we all stand aghast at the mouth of the caves of our deaths; and this is our way in.”

“The Way In”

Dr. Gilbert of Harvard has informed us about the happiness problem, but he has much more to do. The learned doctors of Janaloka, the nine wise “masters of yoga,” understand what he knows and then some. . . .

When the time comes, we should have no uncertainty.