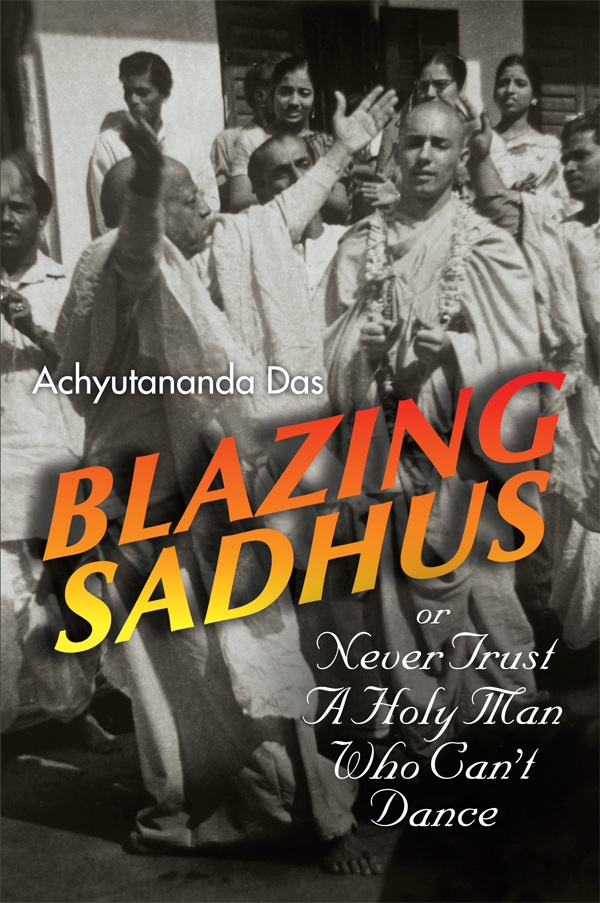

Book Review: Achyutananda Das, “Blazing Sadhus or Never Trust a Holy Man Who Can’t Dance”

By Steven J. Rosen (Satyaraja Dasa) | Dec 11, 2012

Achyutananda Das, “Blazing Sadhus or Never Trust a Holy Man Who Can’t Dance” (Alachua, Florida: CMB Books, 2012), 227 pages, 6 x 9. Available from www.krishna.com

“Practically speaking you were my first disciple, and I think it is Bhaktivinode’s desire that my first disciple shall go to Bengal and revive Krishna Consciousness there.” –Srila Prabhupada, letter to Achyutananda, June 8, 1972

This book has been a long time in the making, beginning, perhaps, with Chatur-mukhi Brahma, the first created being. At the very least, it dates back to the predecessor acharyas in the Gaudiya Sampradaya, who predicted that Vaishnava dharma would come West. More, the seeds of this work were planted by His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada in 1966, when Charles Barnett (later Achyutananda Das) met his guru and committed to his mission and teaching. The book has been unfolding ever since.

I have been following its manifestation since the early 1980s, when in an earlier incarnation it was simply a manuscript called “I’m Not God, You’re Not God: The Autobiography of an American Yogi.” At that time, it was at least twice the size of the book I now hold in my hands, and, at the bidding of a Hollywood advisor, contained assorted mini-dramas, a murder, the life of a Bengali counterpart, and, of course, the compulsory sexual escapade — as well as Gaudiya siddhanta and the history of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON). The final product, which we see today, is much condensed, truer to life, more to the point, and a pleasure to read.

Although the book includes a series of non sequiturs and a bit of irreverent humor (both characteristic of Achyutananda’s uniquely creative thinking process), the text is brilliantly conceived and has much to offer the average reader. It is edgy, like Achyutananda himself. But most importantly, Prabhupada’s teaching comes through loud and clear, mainly through anecdotes and personal experiences. Thus, a careful reading will reveal, among other things, Vaishnava Tattva and how it supersedes the impersonalistic school of thought. The book also reveals the distinction between a “real” guru and its all-too-frequent modern derivative: the charismatic personality who has an air of spirituality but little depth. Achyutananda makes clear that Prabhupada is in the former category, evidenced by his vast learning, dedicated practice, and simple humility. Witness but one example of this latter quality as portrayed in Achyutananda’s book:

There were twelve of us now, and the Swami called all of us to his room.

“Everyone will take one day for dishwashing.”

After some silence, someone raised a hand, “I’ll do Monday.” Someone else volunteered for Tuesday. Then more silence. The Swami raised his hand and said, “I will take Thursdays.” Three hands shot up.

From Prabhupada’s perspective, he was simply one of the devotees, though, in reality, he was so much more. Achyutananda conveys both Prabhupada’s specialness and his humility throughout the book. He is able to convey these subtle truths (and others) because of his unique experiences in Krishna consciousness.

Traveling to India early on, Achyutananda was one of the few who had the virtue of “extended family.”* That is to say, while most devotees had Prabhupada and ISKCON in the West (more than sufficient for the cultivation of Krishna consciousness), Achyutananda benefitted from other great souls as well. Srila Shridhar Maharaja, Srila Madhava Maharaja, and Srila Keshava Maharaja (God-uncles), among others, along with their many disciples (cousins) — and also the mahants of the Sri Vaishnava tradition (distant relatives) — gave him perspective and a broader appreciation of the larger tradition as a whole. In other words, there are numerous advantages in having interaction with a variety of relatives dedicated to the family tradition. In this case, especially, Achyutananda learned much about scriptural teaching, spiritual relationships, and Vedic truth by living amongst his Vaishnava kith and kin in India.

Along similar lines, he was one of the first of the Western devotees to learn Bengali, translating portions of the Chaitanya Bhagavata and various Vaishnava songs (producing ISKCON’s first songbook) for the movement. But the translation work that was most significant was cultural: He was able to make Gaudiya Vaishnavism accessible to the West. Like all of Prabhupada’s early disciples, he was given the charge of explaining the tradition in contemporary language, with nuance and references that would make the teachings intelligible and relevant for modernity. He did it back then, and he does it now, in this book.

Often, the philosophy is expressed almost inconspicuously, hidden in simple exchanges between Prabhupada and a disciple. To cite one example:

Someone asked the Swami a challenging question.

“If you say you have full knowledge, then how many windows are in the Empire State Building?

The Swami challenged back, “How many drops of water are in a mirage?”

Achyutananda, following his guru’s lead, never offers the usual pat answer, nor will he be found guilty of uninspired predictability. He is an original communicator, engaging urban wit and a certain brash writing style, unafraid to broach topics that might be considered somewhat unseemly. For instance, he devotes several colorful pages to, of all things, his first experience of defecating in India — this is known as Squatty Potty, or, alternately, the Asian Squat, and even Paleo Pooping. Similarly, he writes of getting hoodwinked by the Indian equivalent of a Jewish garment salesman. And he’s not about to let the guy get away with it.

This streetwise component comes from his background. We learn of his origins and early influences in the 1950s and 1960s — in New York. He came of age during that special, magical period when Beatniks were turning into Hippies, complete with sex, drugs, and rock-n-roll. All of this impacts his search for God and tints his personality.

More than anything else, it seems, the era informed his love of music. Studying under a Mr. Greenberg, who noted his talent with wind instruments (pranayama?), no one at the time could have possibly predicted his future as a highly accomplished kirtan-wallah, mastering mridanga, kartalas, and that somehow authentically Indian singing voice that would produce consequential Hare Krishna LPs and cassettes — recordings that resounded around the world.

His main refrain, as revealed in this book — a Maha-vakya, or overarching theme — is found on both page 47 and on the back cover: “Do you know what just happened in there? Do you know what he just did? He gave me answers to the most cosmic, theological, universal, eternal questions ever asked! And like it was just matter-of-fact! Then he thanks me for asking! I gotta tell people about this.”

Here we find the central thesis of Achyutananda’s life. His love for Prabhupada is evident throughout, revealed in his enthusiasm during those early meetings and in his superlatives in the above quote. Meeting Prabhupada is what he was waiting for. Period. Prabhupada’s response to his questions revolutionized his life, forming his direction, dedication, and aspirations. Finally: “I gotta tell people about this.” This is the Sankirtan principle in a nutshell. Having imbibed the Truth from a bona fide spiritual master, one wants to share it with others, whether through chanting the holy name in public or explaining the philosophy behind the chanting to one and all. Achyutananda has done both. In spades.

As we see in the pages of Blazing Sadhus, he takes Prabhupada’s teaching and kirtan to Bengal and to Vraja, to South India and back again, all the while growing and learning and sharing what he learns. By the end of the book, WE learn the real secrets of Tantra and Yoga, from rudimentary definitions to the confidential love of Radha and Krishna.

In this way, Achyutananda’s book is successful: We feel as though we are with him on his journey. We accompany him as he reminisces about noodnick high jinx in the Bronx and stoned-out music buddies in the West Village. And we are by his side as he graduates from conventional forms of Yoga to Vaishnavism, taking in and appreciating the most profound philosophy in the three worlds. We “get it” as he explains to us his realizations or ruminates over Prabhupada’s inner teachings. As a result, we can only kvell.

One final point: I found the title intriguing, not just because it is an obvious parody on “Blazing Saddles,” but because the notion of something “blazing” or “on fire” is at the heart of Vaishnava thought. Bhagavad-gita (11.17) describes the Universal Form as having an effulgence that is dipta-anala, like a “blazing fire”; the spiritual master delivers the afflicted world by extinguishing the “blazing fire” of material existence (samsara-davanala-lidha-loka-tranaya karunya-ghanaghanatwam); and Bhaktivinode Thakur sings: “According to the particular relationship and mood manifested during any given lila involving Radha and Krishna, bodily symptoms (sattvika bhava) can take on four different degrees of intensity, namely, (1) dhumyita (smoldering), (2) ujjvalita (ignited), (3) dipta (burning), and (4) uddipta (blazing).” Finally, Rupa Goswami’s ultimate devotional treatise, focusing on the intimate love of Radha and Krishna, is known as Ujjvala-nilamani — “the Blazing Sapphire.” In this case, “blazing” refers to the intensity of Sri Radha’s love, which makes hearts melt and inspires tears of joy. Without doubt, then, this book, coming in that same tradition, can turn one into a blazing sadhu. Read it and see.

__

*The notion of “extended family” indicates that beyond the nuclear family, or the immediate family, one can benefit from the association of grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins, all living nearby or in the same household. In many cultures, particularly in Southern Europe, Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, and so on, extended families constitute the common state of affairs.

__

Satyaraja Dasa (Steven J. Rosen), a disciple of Srila Prabhupada, is a BTG associate editor and founding editor of the Journal of Vaishnava Studies. He has written over thirty books on Krishna consciousness and lives near New York City.